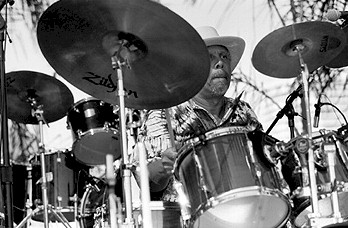

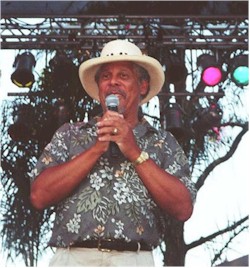

Al Williams

Artist Profile:

Al Williams

Al Williams organized his first band, The Modern Jazz Majors, in college, building a glowing “rep” in local clubs such as The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. As Williams’ popularity grew, he became an in-demand drummer for the likes of Hampton Hawes, Teddy Edwards, Leroy Vinnegar and Roy Ayers. Williams was so proficient, folks started calling him “Baby Boy” because he was so much younger than the heavyweights who hired him.

Al Williams organized his first band, The Modern Jazz Majors, in college, building a glowing “rep” in local clubs such as The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. As Williams’ popularity grew, he became an in-demand drummer for the likes of Hampton Hawes, Teddy Edwards, Leroy Vinnegar and Roy Ayers. Williams was so proficient, folks started calling him “Baby Boy” because he was so much younger than the heavyweights who hired him.

However, by the late `70s, Williams decided two changes were in order: the local club scene and his lifestyle. “When I was traveling,” he reflects, “the clubs we played weren’t really jazz clubs. They were set up for ‘other purposes.’ So when I came off the road to be with my daughter, I decided to build a club specifically for jazz.” Thus, The Jazz Safari – Long Beach’s first jazz club – was born in 1978. “It was intimate and easy to manage,” he remembers. “I could sit in one corner and watch my entire operation.”

1978 was also the year that Williams launched The Queen Mary Jazz Festival, Southern California’s first two-day jazz festival (the April affair beat Playboy’s Jazz Festival by two months), featuring Cal Tjader, Jimmy Witherspoon, Gloria Lynne and Supersax. When the Jazz Safari’s lease wasn’t renewed, Williams bowed out of the clubs and festivals temporarily. When he returned, it was in downtown Long Beach in a bigger, upstairs-with-a-view room that he boldly christened, Birdland West. The club’s sound was so impeccable that Carmen McRae and Freddie Cole recorded live albums there.

Next, Williams returned to the festival scene with the beautiful lagoon as the location, his own Rainbow Promotions company to book it, and a plan that gave him complete control. “This time the land belonged to the city,” he shares, “and I had the festival name patented.” Stanley Clarke and the top-drawing team-up of Eddie Harris & Les McCann were among the acts to inaugurate the 1st Annual Long Beach Jazz Festival in 1987. Outside of the Long Beach Grand Prix, the Long Beach Jazz Festival is the city’s second largest event, according to Benoit. “They’ve ‘grandfathered’ us in, so the second weekend in August is ours for as long as we want it.”

Outside of the Long Beach Grand Prix, the Long Beach Jazz Festival is the city’s second largest event, according to Benoit. “They’ve ‘grandfathered’ us in, so the second weekend in August is ours for as long as we want it.”

Weekend attendance has grown steadily and averages between 25-30,000 over the 3 days. The festival gives back to the city, too, not only in tourism revenues but also in special programs. This year, the Urban League and Downtown Long Beach Associates are doing a “Jazz Talent Search,” the winner of which will open the festival on Sunday. And on Saturday, the Long Beach Poly High School Jazz Band opens the program.

After 15 years, Williams and Benoit have the programming down to a science, with a shrewd blend of contemporary and traditional jazz strains. “I opened the festival up to more smooth jazz acts to appeal to more people,” Al explains, “but I try to make a few be bop converts every year.” Williams is hard-pressed to choose all-time favorites – the artists being friends and all – but one performance was too priceless to forget. “It was Cab Calloway – his last performance,” Williams offers. “It was strange at first. When he got out of the limousine, he was shufflin’, which kinda made me nervous. But as soon as the band struck up, that overcoat flew off, he came runnin’ out hollerin’ ‘Hi De Ho’ and tore the place up!” Beyond the ecstatic audience response, jazz performers have become quite attached to this festival, too. Saxophonist Gerald Albright, who recorded his Live at Birdland West Lp in Williams’ now-closed nightclub, shares, “The Long Beach Jazz Festival is really special for me because I got to see it from its embryonic stage to what it is today. I met Al when I was playing bass guitar for Willie Bobo at the Jazz Safari, so we go back! I’ve played his festival at least eight times. He’s always kept a slot there for me. For me to still be playing his festival is a compliment in itself.” Wayne Henderson, founding trombonist of the Jazz Crusaders, still cites Al’s ears as an element musicians respect and appreciate.

“Sound is a nightmare for musicians at festivals. Al sets a real comfort zone for musicians by relieving them of the stress of worrying about it. Beyond that, Al is just a beautiful human being – always so personable and positive, and always smiling. Even if the roof caved in, somehow he’d find a way to keep smiling.” Musician Kirk Whalum fondly recalls, “I distinctly remember my first festival with Al Williams. I thought it was interesting to have a musician (Al) promoting the concert and championing the cause of live and quality music.

The Long Beach Jazz Festival is one of my favorite festivals to play because they generally have a great line up that always include REAL music. I’m one of the many people who appreciate it.” Asked if it’s gotten any easier to put this show on after 15 years, Benoit muses, “A few years ago it wasn’t very difficult. Now it’s more challenging. There are jazz festivals in every city throughout the summer. To get the quality acts, we really have to start months out now.” All of the hard work and love makes the Long Beach Jazz Festival an outdoor love-in that keeps the people coming back year after year.