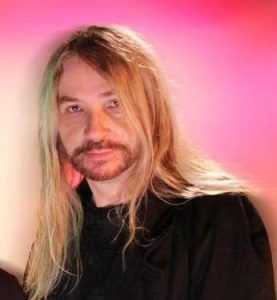

Rob Block

Artist Profile:

Rob Block

Job security and fat paychecks aren’t obvious perks of a career in jazz. In St. Louis, as in most cities around the country, jazz is a niche market, a tiny section of the live-entertainment scene. Too many good musicians compete for too few jobs — and too few venues exist to book them. Not surprisingly, this situation leaves a lot of local talent frustrated, and the more ambitious often end up elsewhere.

Job security and fat paychecks aren’t obvious perks of a career in jazz. In St. Louis, as in most cities around the country, jazz is a niche market, a tiny section of the live-entertainment scene. Too many good musicians compete for too few jobs — and too few venues exist to book them. Not surprisingly, this situation leaves a lot of local talent frustrated, and the more ambitious often end up elsewhere.

Rob Block: “St. Louis is really where I got my ears together, playing with great musicians.”Rob Block’s been relatively successful, despite all the challenges. In addition to locking up long-term gigs with the likes of Willie Akins, Hugh “Peanuts” Whalum and Dave Venn, Block was named Jazz Artist of the Year in the 1998 RFT Slammy Awards. He’s also been teaching as an adjunct instructor in Webster University’s jazz-studies program since 1991. But like so many of his talented peers, he’s decided to leave his hometown for greener pastures; later in February, he and his wife, pianist Tomoko Akiho, will head south to New Orleans.

Local jazz aficionados will certainly miss him. As a guitarist, Block is known for his impeccable phrasing and his rare balance of blazing technique and concise, on-the-mark improvisation. “Rob is an amazing musician,” says Steve Schenkel, one of the area’s best jazz guitarists and a professor at Webster University. “He’s a world-class guitarist, and his touch, tone and time are impeccable. I consider every concert that I play with him like a free guitar lesson.”

As a pianist, Block has made an impact on both the jazz and Latin-music scenes, working with an array of groups. He also led his own Latin jazz band for several months at Club Viva! on Monday nights. In the process, he’s become so proficient at the keyboard that some knowledgeable jazz fans — if forced to choose — would opt for his adventurous piano playing over his dexterous guitar work. “One of the things that makes Rob such an accomplished musician is his skill on both piano and guitar,” explains pianist Venn, who’s played with Block for several years. “He has the experience and understanding to really appreciate what I’m trying to do on piano, and that enables us to work together with such great empathy.”

Block’s St. Louis musical career began in 1987, after he returned to his hometown from California, where he studied jazz composition for almost four years at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. “I had just gone through a broken love affair at school and decided to come back and take a semester off,” Block recalls. “I ended up playing with Willie, then getting married, and the city just sucked me in.”

The newly arrived Block was looking for places to sit in with local musicians, and Joe Schwab, owner of Euclid Records, told him to check out a sax player named Willie Akins at the Barbary Coast. “I went to the club and eventually sat in,” Block says. “I was really nervous, of course, because Willie is very good. I don’t think he was that impressed, but Pauline Stark, who put together bookings for jazz players, told me she was going to book Willie and me together on a gig. She did, and over the course of an entire evening, Willie had a chance to hear what I could do. Luckily he liked it, and I started playing in his band.”

Block’s six-string skills became a standard feature in Akins’ lineup, and that opportunity led to the formation of another band, the Kirby-Block Project. Bassist Steve Kirby, also a member of Akins’ group at the time, began working with Block as a duo when they weren’t performing with Willie. Kirby and Block eventually expanded the group and ended up playing almost every night, sometimes cramming two gigs into an evening.

That exposure led to regular jobs at Just Jazz and to steady work with veteran sax player Whalum at the Adam’s Mark Hotel. But the regular paycheck for that gig had its trade-offs for Block. “I knew that after Jan. 1, when the bottom falls out for most musicians, I still had a gig,” Block says. “And playing with Peanuts and musicians like Charles Fox, I picked up on so many tunes, was forced to hear faster and to learn how to transpose really quickly. But the bad thing was that I was there for nine years, and that made me almost invisible on the club scene.”

Combined with the teaching job he picked up in Webster University’s jazz-studies program in 1991, Block found he had little time to lead groups, which was frustrating because he’d built up a stack of his own compositions. When he did find the time to perform, Block discovered that there was less demand for groups that focused on original compositions rather than the standard repertoire. “It can be really rough,” he says. “What a lot of people think of as jazz really isn’t, in my mind. So you assume there are a variety of venues to play, but when it comes to real jazz, there aren’t. And I’ve also seen a decline in the number of those places over the last couple of years. Plus, when you’re playing original music, you have to get the musicians in your band to do rehearsals. If you’re not getting that much money in the first place, it’s difficult to ask them to make that commitment.”

These are problems all musicians face, whether they live in St. Louis or not, but Block and his wife are expecting a child, which forced them to take a hard look at their financial situation. Block, who doesn’t hold an advanced degree, is limited to an adjunct teaching role at Webster, which means a limited salary and benefits. Having made important contacts in New Orleans, a city with a stronger music scene and equally impressive academic opportunities, Block decided to relocate.

“I discovered I was pretty good at teaching,” he explains. “And I enjoyed doing it at Webster. But I realized I was going to have to get a master’s to really get anywhere in the field. The University of New Orleans has a great music school, and Steve Masakowski, who’s a tremendous guitarist, teaches there. In New Orleans I’ll also have a greater opportunity to work with players doing original music. People there seem to be more accepting of that in clubs.”

Looking back on his experience in St. Louis, Block acknowledges both the positive and negative aspects of life as a jazz musician. What sticks out most for him are the benefits he’s gained from working with talented musicians he believes most St. Louisans overlook. “In retrospect, it’s been great,” he says. “I don’t remember what I was playing like when I first came back, but it’s definitely on a much higher level now. St. Louis is where I really got my ears together, playing with great musicians like Willie [Akins], Dave Venn, Freddie Washington, Eddie Fritz and others. There’s some really great players here that people have gone to sleep on.”

The same could be said of Block himself. But even if the city at large is snoozing, other musicians will miss him. Carol Schmidt, a member of the defunct group Jasmine, has taken jazz-piano lessons from Block for the past four years. “I’ve known a lot of great musicians in my life,” Schmidt says, “but I can count the musical artists I’ve met on one hand, and Rob is one of them. He doesn’t use acquired skills and musicianship to re-create a style. Instead, he’s one of those rare artists who actually creates something new.”

If you want to witness such rare artistry for yourself, you’ll have plenty of opportunities over the next week. Block and Schenkel perform as a duo on Monday, Feb. 11, at Webster University’s Winifred Moore Auditorium; the guitarists will improvise on tunes submitted to them by the audience. On Wednesday, Feb. 13, Block brings together many of the musicians he’s performed with over the years for an official farewell concert. And you can bet that whether he’s playing Cuban jazz, bop or Brazilian samba, he’ll be throwing plenty of his original compositions into the mix.