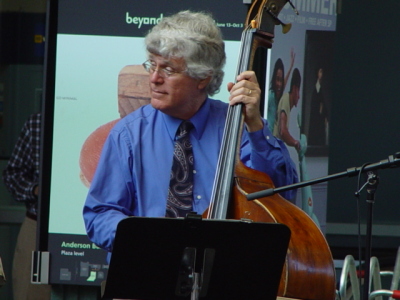

Harvey Newmark

He believes that doubling up between jazz and the classics makes him a better player on both sides of the street. “The classics demand discipline and jazz requires improvisation, and together they wipe out the old bromide, ‘It’s close enough for jazz,’ when a jazz musician laughs off a clam,” Newmark said. “Close is never acceptable if with a little work you can get it right.” Newmark started playing gigs at 14, and four years later turned down an offer from bop clarinetist Buddy DiFranco to join his band.

He believes that doubling up between jazz and the classics makes him a better player on both sides of the street. “The classics demand discipline and jazz requires improvisation, and together they wipe out the old bromide, ‘It’s close enough for jazz,’ when a jazz musician laughs off a clam,” Newmark said. “Close is never acceptable if with a little work you can get it right.” Newmark started playing gigs at 14, and four years later turned down an offer from bop clarinetist Buddy DiFranco to join his band.

“I wanted to finish my education, and at the time, saying no to Buddy seemed like the right thing to do,” he said. “But I’ve lived to regret that decision and I still do.” How did DiFranco hear about him? “Darned if I know,” said Newmark, who was born, raised and educated in Los Angeles, where he still lives.

“It could be my name was floating out there. It happens, and you never know about it until you get a call.” He attended three universities in Southern California, but never stayed at any of them long enough to obtain a degree. He continues to study privately, the past 20 years with the same person, and it’s paid off. He is principal bassist for two of the four symphonies with which he plays, and he has been performing with the Long Beach Symphony Orchestra for 24 years. His resume shows he’s also worked with such respected jazz artists as Harry Edison, Anita O’Day, Red Holloway and Laurindo Almeida.

“When you freelance, you have to be ready for whatever comes your way, and I mean whatever,” Newmark said. “After all, how many musicians do you know who worked with Buddy Rich and Lawrence Welk in the same month? I did. Talk about playing for guys living in two different worlds.” With Rich, who was often described as having the disposition of a spoiled kid because of his tirades against his musicians, he played a two-week gig subbing for the regular bassist.

Newmark felt he got off easy because Buddy seemed to like him. “As far as I know, he only blew his top once during the time I was on the band, and then I didn’t see the flare-up.” But what he did get to see every time the band took the stage was an uncluttered view of Rich in action. “I was standing right next to him, only on a slightly lower level —- so when Buddy took off, there were those sticks flying overhead,” he said. “It was a force of nature.” Newmark worked with Welk for only a week, but it was long enough to appreciate his kindness and his skills.

“Lawrence treated everyone the same, even though there were enough … marriages among band members it made it seem more of a family than anything else,” Newmark said. “And working with Lawrence only confirmed what I had said all along: ‘You may not like his music, but he’s a good musician.’ He had to be, to hire all those great musicians and know what would and wouldn’t work.” Given a choice between playing jazz or the classics, what would Newmark pick? “I wouldn’t want to give up either one, even if I could,” he said. “But I do know this: If I were to become a full-time classical musician, I’d still play jazz, if only to entertain myself.